Order dimension

In mathematics, the dimension of a partially ordered set (poset) is the smallest number of total orders the intersection of which gives rise to the partial order. This concept is also sometimes called the order dimension or the Dushnik–Miller dimension of the partial order. Dushnik & Miller (1941) first studied order dimension; for a more detailed treatment of this subject than provided here, see Trotter (1992).

Contents |

Formal definition

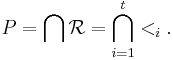

The dimension of a poset P is the least integer t for which there exists a family

of linear extensions of P so that, for every x and y in P, x precedes y in P if and only if it precedes y in each of the linear extensions. That is,

Realizers

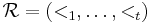

A family  of linear orders on X is called a realizer of a poset P = (X, <P) if

of linear orders on X is called a realizer of a poset P = (X, <P) if

,

,

which is to say that for any x and y in X, x <P y precisely when x <1 y, x <2 y, ..., and x <t y. Thus, an equivalent definition of the dimension of a poset P is "the least cardinality of a realizer of P."

It can be shown that any nonempty family R of linear extensions is a realizer if and only if, for every critical pair (x,y) of P, y <i x for some order <i in R.

Example

Let n be a positive integer, and let P be the partial order on the elements ai and bi (for 1 ≤ i ≤ n) in which ai ≤ bj whenever i ≠ j, but no other pairs are comparable. In particular, ai and bi are incomparable in P; P can be viewed as an oriented form of a crown graph. The illustration shows an ordering of this type for n = 4.

Then, for each i, any realizer must contain a linear order that begins with all the aj except ai (in some order), then includes bi, then ai, and ends with all the remaining bj. This is so because if there were a realizer that didn't include such an order, then the intersection of that realizer's orders would have ai preceding bi, which would contradict the incomparability of ai and bi in P. And conversely, any family of linear orders that includes one order of this type for each i has P as its intersection. Thus, P has dimension exactly n. In fact, P is known as the standard example of a poset of dimension n, and is usually denoted by Sn.

Order dimension two

The partial orders with order dimension two may be characterized as the partial orders whose comparability graph is the complement of the comparability graph of a different partial order (Baker, Fishburn & Roberts 1971). That is, P is a partial order with order dimension two if and only if there exists a partial order Q on the same set of elements, such that every pair x, y of distinct elements is comparable in exactly one of these two partial orders. If P is realized by two linear extensions, then partial order Q complementary to P may be realized by reversing one of the two linear extensions. Therefore, the comparability graphs of the partial orders of dimension two are exactly the permutation graphs, graphs that are both themselves comparability graphs and complementary to comparability graphs.

The partial orders of order dimension two include the series-parallel partial orders (Valdes, Tarjan & Lawler 1982).

Computational complexity

It is possible to determine in polynomial time whether a given finite partially ordered set has order dimension at most two, for instance, by testing whether the comparability graph of the partial order is a permutation graph. However, for any k ≥ 3, it is NP-complete to test whether the order dimension is at most k (Yannakakis 1982).

Incidence posets of graphs

The incidence poset of any undirected graph G has the vertices and edges of G as its elements; in this poset, x ≤ y if either x = y or x is a vertex, y is an edge, and x is an endpoint of y. Certain kinds of graphs may be characterized by the order dimensions of their incidence posets: a graph is a path graph if and only if the order dimension of its incidence poset is at most two, and according to Schnyder's theorem it is a planar graph if and only if the order dimension of its incidence poset is at most three (Schnyder 1989).

References

- Baker, K. A.; Fishburn, P.; Roberts, F. S. (1971), "Partial orders of dimension 2", Networks 2 (1): 11–28, doi:10.1002/net.3230020103.

- Dushnik, Ben; Miller, E. W. (1941), "Partially ordered sets", American Journal of Mathematics 63 (3): 600–610, doi:10.2307/2371374, JSTOR 2371374.

- Schnyder, W. (1989), "Planar graphs and poset dimension", Order 5 (4): 323–343, doi:10.1007/BF00353652.

- Trotter, William T. (1992), Combinatorics and partially ordered sets: Dimension theory, Johns Hopkins Series in the Mathematical Sciences, The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801844256.

- Valdes, Jacobo; Tarjan, Robert E.; Lawler, Eugene L. (1982), "The recognition of series parallel digraphs", SIAM Journal on Computing 11 (2): 298–313, doi:10.1137/0211023.

- Yannakakis, Mihalis (1982), "The complexity of the partial order dimension problem", SIAM Journal on Algebraic and Discrete Methods 3 (3): 351–358, doi:10.1137/0603036.